CCA: A Greener Grid

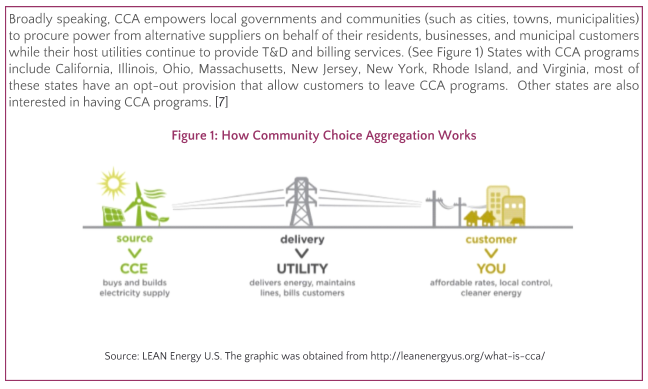

Community Choice Aggregation (CCA), while not new, has started receiving attention only recently. Since the late 1990s and early 2000, some states have enacted legislation involving CCA as part of their electricity industry restructuring and retail choice. [1] In the past two years, CCA programs have grown considerably in several states to increase customers’ choices in clean energy procurement, with the goals of reducing carbon emissions, creating local jobs, and reducing electricity bills. Nevertheless, CCAs have faced some challenges.

Community Choice Aggregation (CCA): Influencing A Greener Grid

Dozens of cities and towns in Massachusetts, for instance, have either adopted CCA programs or are working to set up CCA programs. [2] The city of Boston, for example, is in a process of setting up Community Choice Energy (CCE). [3] Like other neighboring cities and towns, it plans to procure more than the minimum level of renewable energy required by Massachusetts regulation (at least 12% of Class I renewables). [4] In addition, it expects the cost of customers’ electricity bills to decrease. According to the Applied Economics Clinic, Boston’s nearby towns were able to lower their power supply costs in the first half of 2018 by 18% of the basic supply service rate. [5] However, the cost savings of procuring power from competitive retail electricity providers relative to incumbent utilities’ basic service rates could dissipate if an incumbent utility matches or provides a lower cost of supplies, and/or if CCA faces demand charges. Illinois’ CCA programs experienced some of these challenges, resulting in a slowdown of the state’s CCA activities.

During 2012-2013, Illinois’ CCA programs were the fastest growing in the U.S. among residential customers due to the cost advantages. [5, 6] Over 700 communities in Illinois formed CCAs by mid-2014, and more than 70 percent of residential and small commercial customers in Commonwealth Edison’s service area participated in CCA. Retail electricity suppliers provided power to approximately 54% of residential customers. However, by 2015, the cost advantage disappeared, and 100 CCAs (16% of residential customers) returned to their incumbent utilities. By 2017, only 35% of residential customers were served by retail electricity suppliers. [6]

Unlike Illinois and Massachusetts, California suspended its full retail choice in 2001. Three California investor-owned utilities (IOUs) have obligations to serve load in their service areas. Nevertheless, large nonresidential customers have direct access to competitive suppliers with limited volume. [8] In 2002, the California legislature, through AB117, required the CPUC to make CCA possible in California. The first CCA operational program began serving customers in Marin County in May 2010. The number of CCAs jumped by threefold between 2017 and 2018, in which 15 new CCA programs started in California. This compares to five CCA programs at the end of 2016. [9] The 2018 CCA load is approximately 10 percent of the total California electricity consumption, with an estimated (non-coincident) peak load of over 6,000 MW. [10] California’s CCA load is expected to rise to 16 percent by 2020. [11]

A fast growing number of CCA programs could significantly alter the landscapes of IOUs as the IOUs have entered in long-term purchase power agreements (PPAs) to serve load. Because of this, a portion of IOUs’ load becomes CCAs’ load, resulting in excess capacity for IOUs. PG&E, for instance, forecasted that by 2020 it will only provide retail electric service to approximately 45% of the total electric load in its service area. [13]

Nevertheless, like other California load serving entities, the California CCAs are subject to the Renewables Portfolio Standard (RPS), Integrated Resource Planning (IRP), and resource adequacy requirements. They also have to meet the new RPS goal of 100% of all retail sales by 2045 that was passed by the California Legislature (Senate Bill 100, [14]). Obtaining 100% renewable resources is not a barrier to these CCA programs. In fact, a typical California CCA resource mix is generally composed of renewables (wind, solar, geothermal etc.), hydro, conventional energy, energy storage, distributed energy resources, demand response, and energy efficiency programs. [12] The challenge for them, however, is how to finance long-term PPAs to comply with Senate Bill 350, which requires that 65% of the RPS resources must be from long-term PPAs of 10 years duration or longer. Portfolios of the California start-up CCAs currently consists of shorter-term PPAs. [15] They will need to work together with their IOUs and the California Public Utilities Commission to find sound economics and sustainable solutions to ensure grid reliability during this transition period.

Comments to this information can be sent to info@rpbenergyeconomics.com

_________________________